The legacy of Phylloxera: The root of Europe’s viticulture

In the annals of European viticulture, one name stands out as the herald of disruption and transformation: Phylloxera. This minuscule insect, native to North America, made its fateful arrival in Europe’s vineyards during the 1860s, leaving in its wake a trail of devastation that forever altered the European viticultural landscape.

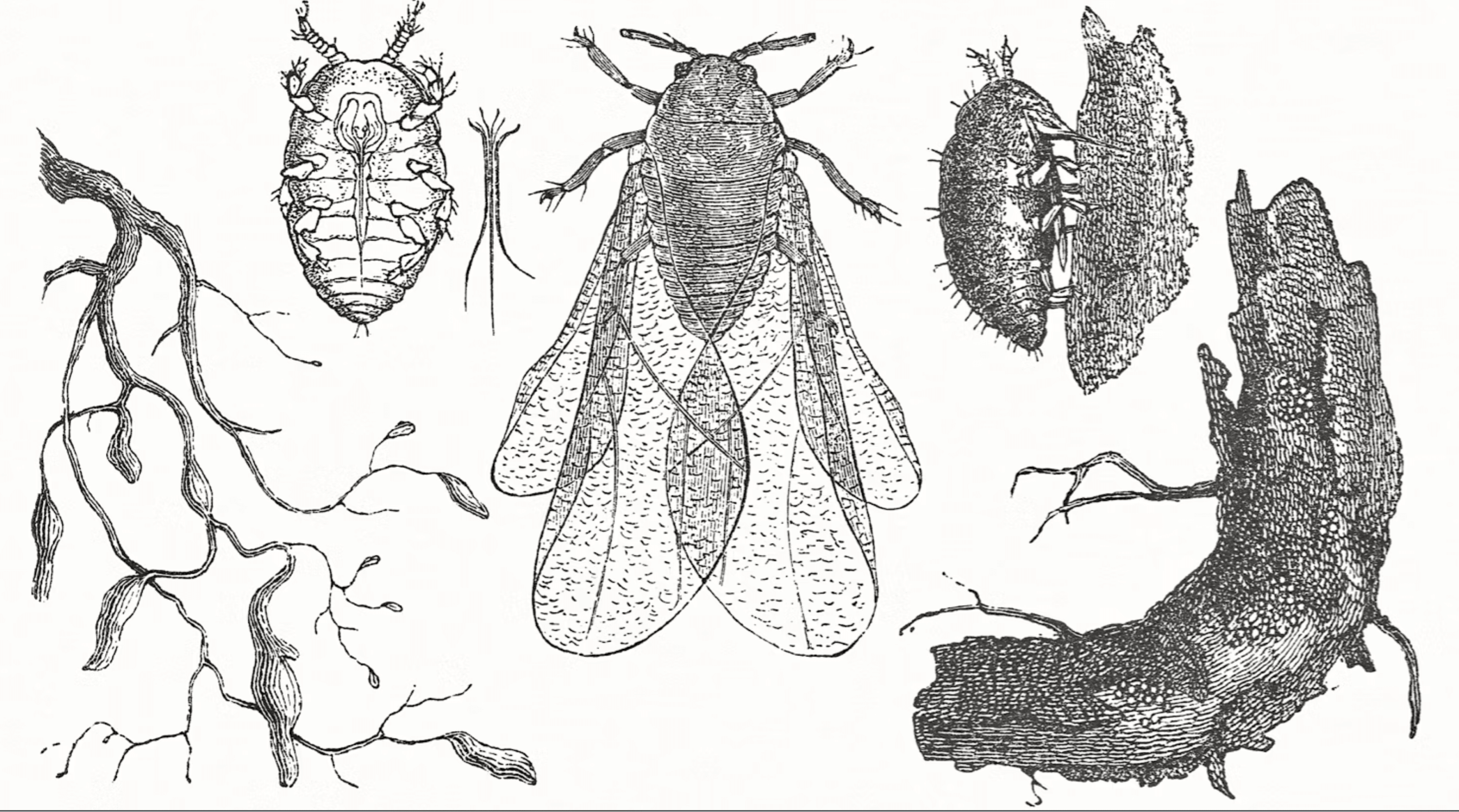

Phylloxera is a microscopic aphid-like insect, made its journey to European vineyards by hitching a ride on imported American vine cuttings. The impact of the Phylloxera infestation was nothing short of catastrophic. As these insects fed on the roots of grapevines, they sapped the vitality of the vines, ultimately leading to their demise. Entire vineyards were decimated, resulting in a staggering loss of grape production.

What did the viticulturist and vigneron do?

In response to this crisis at first a quick fix was to blend grapes from regions not affected by Phylloxera (Yet) famous examples are Shyraz from the Rhone blended into Bordeaux and Nebbiolo and Nerello into Burgundy – we don’t know what percentage those blend represented as nobody at the time was publicly announcing the deed but we know that they happened.

European winegrowers found only one suitable solution: they grafted native Vitis Vinifera vines onto American rootstocks, which are able to resist Phylloxera as they evolved to grow thicker root skins and more sappy which repelled Phylloxera. This monumental undertaking not only saved European viticulture but also established new standards for viticulture worldwide.

In historical regions, such as the Cote de Nuits, Pinot Noir asserted dominance, while Nebbiolo took root in the Langhe regions at the same time it meant that some varieties were being abandoned.

Fun fact – The beautiful rows of vines that we see now are also a result of phylloxera and the extensive replacement of Vine happened at once!

While grafting onto American rootstocks became the prevailing strategy, certain lucky few European vineyards are able to retain their own-rooted vines. These vineyards occupy special spots where Phylloxera couldn’t establish itself, owing to unique soil conditions (such as sand) or because the vineyards were sufficiently isolated to prevent the insect’s spread.

Own-rooted vines in Europe stand in as a testament to the ancient methods of viticulture. They often provide a direct link to historical grape varieties of a region. These vines offer authenticity that some winemakers and consumers find alluring.

One of the most sought-after Italian Own Rooted as they are known for is the Pie Franco of Dott. G. Cappellano in Barolo the rightly named Pie Franco, a project started in the 1980s with only a handful of rows planned in on their own roots in the famous Gabutti vineyard in the heart of Barolo this is the only example known to exist in the Barolo Region. This barolo is extremely limited in its production and it is known for its robustness and vibrancy.

Although, a rarity in the wine world, ungrafted wines have found their way to our shop

Discover the world’s finest wines with Crurated’s exclusive membership. Access rare allocations, secure storage, and personalized wine concierge services. Join today the elite club of discerning wine enthusiasts.